Image 1 of 9

Image 1 of 9

Image 2 of 9

Image 2 of 9

Image 3 of 9

Image 3 of 9

Image 4 of 9

Image 4 of 9

Image 5 of 9

Image 5 of 9

Image 6 of 9

Image 6 of 9

Image 7 of 9

Image 7 of 9

Image 8 of 9

Image 8 of 9

Image 9 of 9

Image 9 of 9

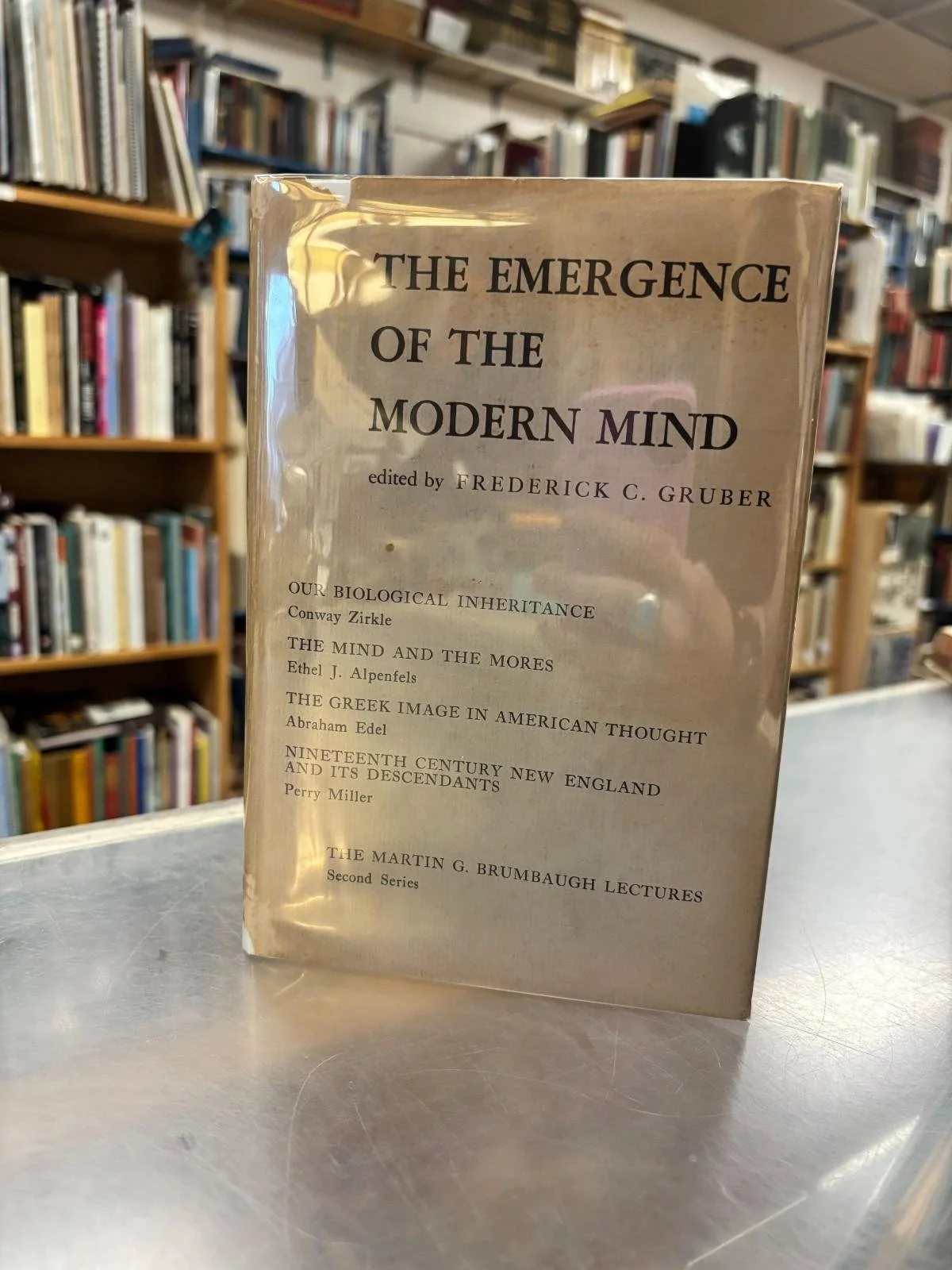

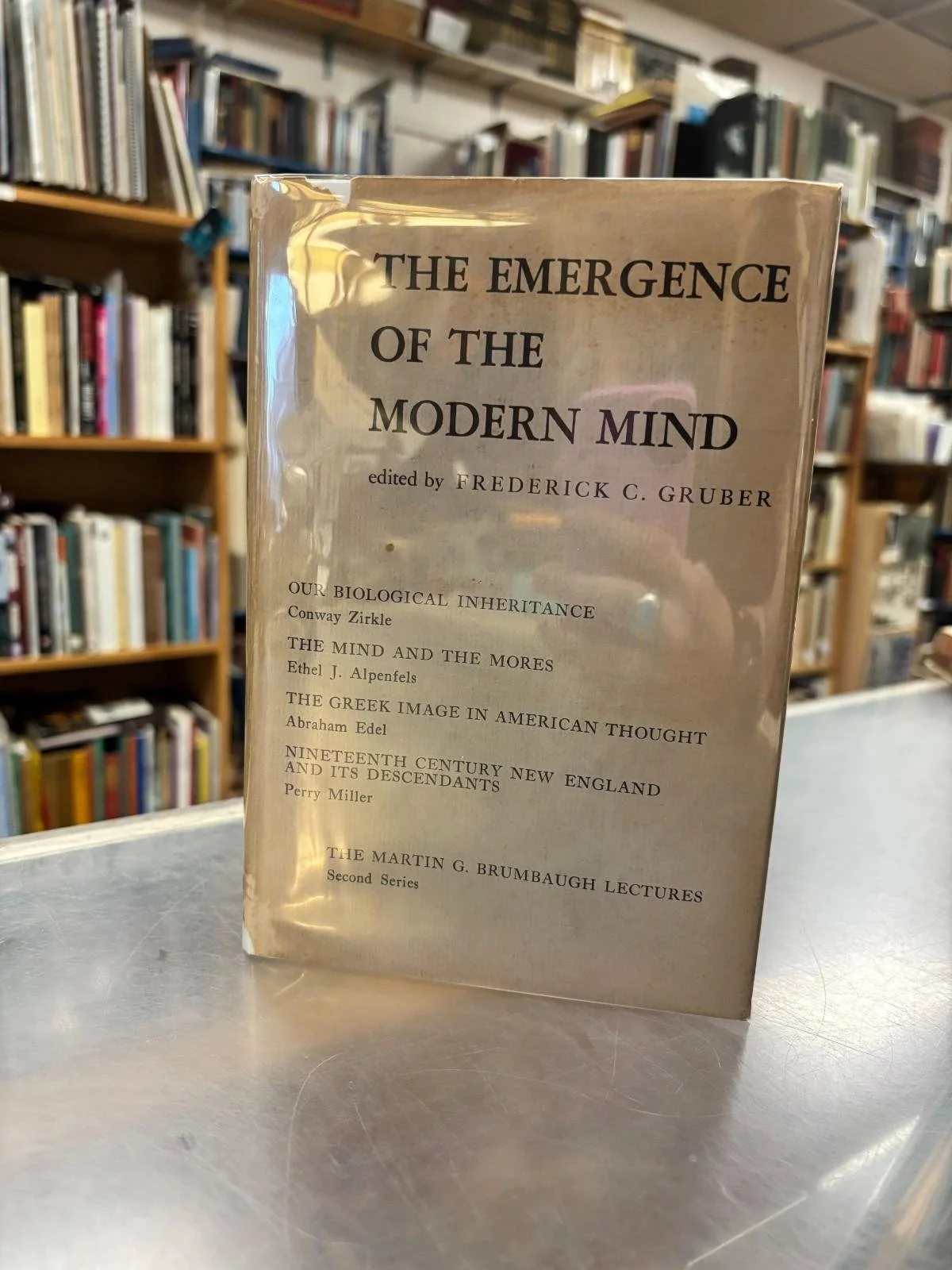

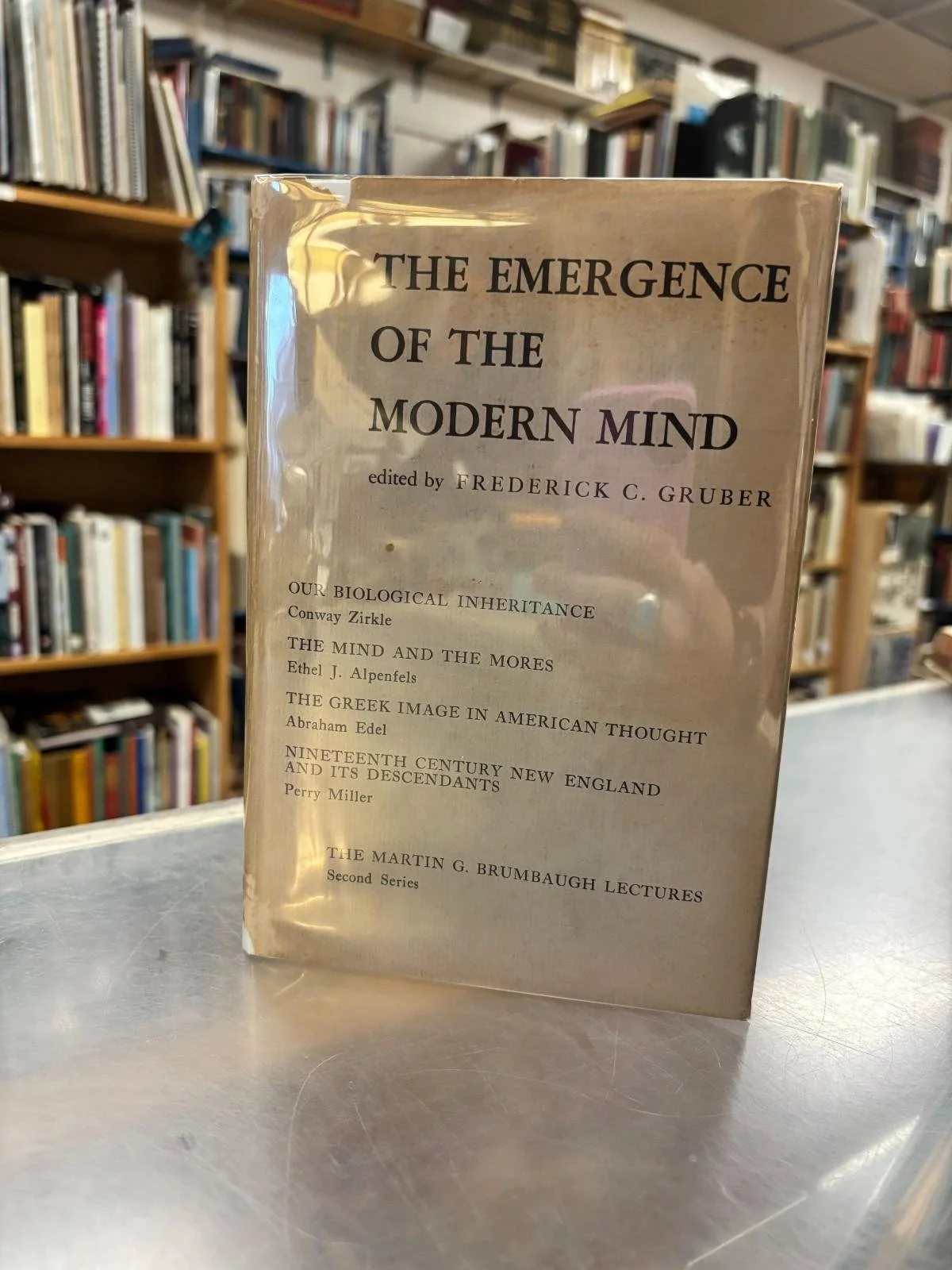

1958 THE EMERGENCE OF THE MODERN MIND Gruber, F. 1st ed.

What is the modern mind? The essays in this volume-originally delivered as the Second Series of the Martin G. Brum-baugh Lectures in Education at the University of Pennsylvania-offer illuminating answers to this question by a biologist, an anthropologist, a philosopher, and a literary historian, each of whom approaches the question in light of his own study and experience.

In "Our Biological Inheritance," Conway Zirkle points out that man is an animal, but that he is also unique in living at the same time in a biological and social world. He states further that, although individuals do not breed true, large groups do, so that through "population genetics" the hereditary potentials of groups can be determined. Ethel J. Alpenfels' "The Mind and the Mores" examines the relationship of the individual to society and finds that the source of culture is the stuff of human experience, for no person originates his own culture. Although she takes note of the struggle toward conformity of ideas after World War II, Professor Alpenfels believes that conformity in America exists basically in material things and social usage. In "The Greek Image in American Thought," Abraham Edel states that there is an increasing interest in Greek thought because America needs ideas. However, he opposes the tendency to make Plato a cult for aristocracy or to link Aristotle to Aquinas as the unerring guide to the solution of modern problems, and recommends a revived interest in Greek civilization from the human standpoint. "Nineteenth Century New England and Its Descend-ants" by Perry Miller stresses the increasing influence of Thoreau over Emerson and indicates that we can find much inspiration in Thoreau's writings and in his view of nature and life.

Each of these essays is a provocative expression of the beliefs and conclusions of four eminent educators who have a great deal to say about what the modern mind has inherited from the past. Professor Zirkle maintains that man's variability is his most precious possession. Professor Alpenfels believes that we must overcome the lag between the physical and social sciences, and that we should develop a formula for smashing prejudices as we developed one for smashing atoms. Professor Edel urges that we should go to the Greeks, not for answers, but for ideas. And Professor Miller suggests that a lead to future development will be found in the vitality and challenge of Thoreau.

What, then is the modern mind? To quote from Frederick C. Gruber's introduction to this volume: "It is a biological and cultural unity. It is one with nature.

It is the product of the past and the promise of the future. It is all that it has been and all that it will be."

What is the modern mind? The essays in this volume-originally delivered as the Second Series of the Martin G. Brum-baugh Lectures in Education at the University of Pennsylvania-offer illuminating answers to this question by a biologist, an anthropologist, a philosopher, and a literary historian, each of whom approaches the question in light of his own study and experience.

In "Our Biological Inheritance," Conway Zirkle points out that man is an animal, but that he is also unique in living at the same time in a biological and social world. He states further that, although individuals do not breed true, large groups do, so that through "population genetics" the hereditary potentials of groups can be determined. Ethel J. Alpenfels' "The Mind and the Mores" examines the relationship of the individual to society and finds that the source of culture is the stuff of human experience, for no person originates his own culture. Although she takes note of the struggle toward conformity of ideas after World War II, Professor Alpenfels believes that conformity in America exists basically in material things and social usage. In "The Greek Image in American Thought," Abraham Edel states that there is an increasing interest in Greek thought because America needs ideas. However, he opposes the tendency to make Plato a cult for aristocracy or to link Aristotle to Aquinas as the unerring guide to the solution of modern problems, and recommends a revived interest in Greek civilization from the human standpoint. "Nineteenth Century New England and Its Descend-ants" by Perry Miller stresses the increasing influence of Thoreau over Emerson and indicates that we can find much inspiration in Thoreau's writings and in his view of nature and life.

Each of these essays is a provocative expression of the beliefs and conclusions of four eminent educators who have a great deal to say about what the modern mind has inherited from the past. Professor Zirkle maintains that man's variability is his most precious possession. Professor Alpenfels believes that we must overcome the lag between the physical and social sciences, and that we should develop a formula for smashing prejudices as we developed one for smashing atoms. Professor Edel urges that we should go to the Greeks, not for answers, but for ideas. And Professor Miller suggests that a lead to future development will be found in the vitality and challenge of Thoreau.

What, then is the modern mind? To quote from Frederick C. Gruber's introduction to this volume: "It is a biological and cultural unity. It is one with nature.

It is the product of the past and the promise of the future. It is all that it has been and all that it will be."